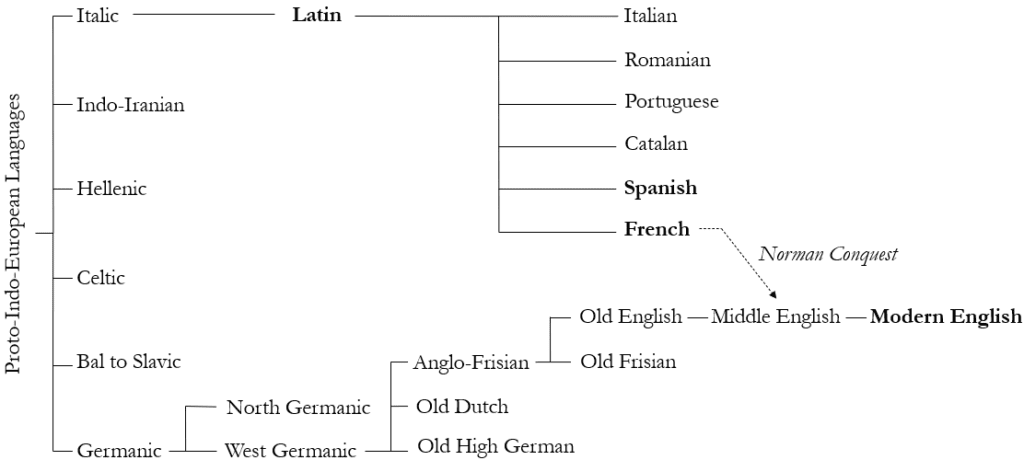

This comparative grammar lesson of Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French covers the similarities and differences between these Romance languages and the English language including cognates and false friends. English is a Germanic language, whereas Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French are Romance languages. Yet, English shares a substantial amount of vocabulary with Romance languages. The main reason is due to the Norman Conquest of England in the eleventh century, as a result of which, the English language borrowed a lot of French words. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) famously claimed that “English is just badly pronounced French.”

French is a Romance language and shares Latin roots, and thus a lot of vocabulary, with Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian. You can see the connection here between these languages and English via the French language. This is why the US Foreign Service Institute (FSI), which provides language training to diplomats and government employees, ranks Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French in the easiest language learning category for English speakers.

Table of Contents

- English Cognates in Romance Languages

- False Friends

- Negation

- Uses of the Written Accents in Romance Languages

- Punctuation

- Abbreviations

- Capitalization

- Level I – Basic

English Cognates in Romance Languages

History aside, we can capitalize on this connection. There are a lot of English cognates in the Romance languages. English cognates are words that are directly descended from a common ancestor language, in this case, mostly French. Moreover, since English has become a universal language, some English words have obviously found their way directly into many languages, including Romance languages.

As we delve into the English cognates, do not feel overwhelmed with the vocabulary. Do not expect to memorize all of the cognates at this basic level. This is just to give you an idea about the similarities with English. This should help provide you a sense of the Romance languages based on prior knowledge of English.

Take, for example, the Latin verb “claudere,” meaning “to close.” In the development of the Italian language, the “l” preceded by a consonant, e.g., “cl,” “pl,” “fl,” etc., has often changed to “i.” Knowing that, you would be more likely to recognize the similarity between the adjectives “chiuso” (pronounced “kyoo-zo”) in Italian and “closed” in English, both derived from the Latin “claudere.” Similar is the case with words such as “fiamma” (flame), “fiore” (flower), and “piazza” (square or place).

From Latin “F” to Spanish “H”

Many words that begin with “h” in Spanish correspond to words that begin with “f” in Portuguese, Italian, and French, which is the original spelling in the Latin source. Here are some examples:

| EN | SP | PT | IT | FR | Latin |

| to do | hacer | fazer | fare | faire | facĕre |

| falcon | halcón | falcão | falcone | faucon | falco |

| hunger | hambre | fome | fame | faim | fames |

| liver | hígado | fígado | fegato | foie | ficātum |

| fig | higo | figo | fico | figue | ficus |

| flour | harina | farinha | farina | farine | farīna |

| thread | hilo | fio | filo | fil | filum |

| aunt | hormiga | formiga | formica | fourmi | formīca |

| oven | horno | forno | forno | four | furnus |

| smoke | humo | fumaça | fumo | fumée | fumus |

| to flee | huir | fugir | fuggire | fuir | fugĕre |

Here, we list some parallels between English and words in the four Romance languages covered in these lessons. We hope that will make you realize how many words you already know or perhaps are able to guess correctly.

List of English Cognates in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French

It is also important to note that these are not strict rules, but rather useful guidelines to make learning Romance languages easier for English speakers.

| EN | SP | PT | IT | FR | Examples | |

| -ile | -il | -il | -ile | -ile | SP | ágil, frágil, hostil |

| PT | ágil, frágil, hostil | |||||

| IT | agile, fragile, ostile | |||||

| FR | agile, fragile, hostile | |||||

| -or | -or | -or | -ore | -eur -eure | SP | interior, favor |

| PT | interior, favor | |||||

| IT | interiore, favore | |||||

| FR | intérieur, faveur | |||||

| -ble | -ble | -vel | -bile | -ble | SP | notable, posible |

| PT | notável, possível | |||||

| IT | notabile, possibile | |||||

| FR | notable, possible | |||||

| -al | -al | -al | -ale | -al -ale | SP | animal, canal, local |

| PT | animal, canal, local | |||||

| IT | animale, canale, locale | |||||

| FR | animal, canal, local | |||||

| -ical | -ico -ica | -ico -ica | -ico -ica | -ique | SP | crítico, lógico |

| PT | crítico, lógico | |||||

| IT | critico, logico | |||||

| FR | critique, logique | |||||

| -ic | -ico -ica | -ico -ica | -ico -ica | -ique | SP | público, romántico |

| PT | público, romântico | |||||

| IT | pubblico, romantico | |||||

| FR | publique, romantique | |||||

| -ant | -ante | -ante | -ante | -ant -ante | SP | elegante, importante |

| PT | elegante, importante | |||||

| IT | elegante, importante | |||||

| FR | élégant, important | |||||

| -ent | -ente | -ente | -ente | -ent -ente | SP | inteligente, diferente |

| PT | inteligente, diferente | |||||

| IT | intelligente, differente | |||||

| FR | intelligent, différent | |||||

| -ment | -mento | -mento | -mento | -ment | SP | documento, elemento |

| PT | documento, elemento | |||||

| IT | documento, elemento | |||||

| FR | document, élément | |||||

| -ist | -ista | -ista | -ista | -iste | SP | artista, dentista, turista |

| PT | artista, dentista, turista | |||||

| IT | artista, dentista, turista | |||||

| FR | artiste, dentiste, touriste | |||||

| -am | -ama | -ama | -amma | -amme | SP | diagrama, programa |

| PT | diagrama, programa | |||||

| IT | diagramma, programma | |||||

| FR | diagramme, programme | |||||

| -em | -ema | -ema | -ema | -ème | SP | problema, sistema |

| PT | problema, sistema | |||||

| IT | problema, sistema | |||||

| FR | problème, système | |||||

| -ous | -oso -osa | -oso -osa | -oso -osa | -eux -euse | SP | curioso, famoso |

| PT | curioso, famoso | |||||

| IT | curioso, famoso | |||||

| FR | curieux, fameux | |||||

| -ry | -rio -ria | -rio -ria | -rio -ria | -aire | SP | contrario, imaginario |

| PT | contrário, imaginario | |||||

| IT | contrario, immaginario | |||||

| FR | contraire, imaginaire | |||||

| -tion | -ción | -ção | -zione | -tion | SP | condición, nación |

| PT | condição, nação | |||||

| IT | condizione, nazione | |||||

| FR | condition, nation | |||||

| -tional | -cional | -cional | -zionale | -tionnel -tionnelle | SP | condicional, racional |

| PT | condicional, racional | |||||

| IT | condizionale, razionale | |||||

| FR | conditionnel, rationnel | |||||

| -tial | -cial | -cial | -ziale | -tiel -tielle | SP | esencial, parcial |

| PT | essencial, parcial | |||||

| IT | essenziale, parziale | |||||

| FR | essentiel, partiel | |||||

| -ce | -cia | -ça | -za -zia | -ce | SP | diferencia, justicia |

| PT | diferença, justiça | |||||

| IT | differenza, giustizia | |||||

| FR | différence, justice | |||||

| -cy | -cia | -cia | -za -zia | -ce -tie | SP | agencia, democracia |

| PT | agência, democracia | |||||

| IT | agenza, democrazia | |||||

| FR | agence, démocratie | |||||

| -ty | -dad | -dade | -tà | -té | SP | autoridad, unidad |

| PT | autoridade, unidade | |||||

| IT | autorità, unità | |||||

| FR | autorité, unité | |||||

| -ly | -mente | -mente | -mente | -ment | SP | totalmente, normalmente |

| PT | totalmente, normalmente | |||||

| IT | totalmente, normalmente | |||||

| FR | totalement, normalement | |||||

| -phy | -fía | -fia | -fia | -phie | SP | filosofía, fotografía |

| PT | filosofia, fotografia | |||||

| IT | filosofia, fotografia | |||||

| FR | philosophie, photographie | |||||

| -sion | -sión | -são | -sione | -sion | SP | decisión, conversión |

| PT | decisão, conversão | |||||

| IT | decisione, conversione | |||||

| FR | décision, conversion | |||||

| -ism | -ismo | -ismo | -ismo | -isme | SP | comunismo, organismo |

| PT | comunismo, organismo | |||||

| IT | comunismo, organismo | |||||

| FR | communisme, organisme | |||||

| -id | -ido -ida | -ido -ida | -ido -ida | -ide | SP | ávido, fluido, sólido |

| PT | ávido, fluido, sólido | |||||

| IT | avido, fluido, solido | |||||

| FR | avide, fluide, solide | |||||

| -ive | -ivo -iva | -ivo -iva | -ivo -iva | -if -ive | SP | activo, nativo, negativo |

| PT | ativo, nativo, negativo | |||||

| IT | attivo, nativo, negativo | |||||

| FR | actif, natif, négatif | |||||

False Friends

Although cognates will often have the same meaning as in English, it is important to note that this is not always the case, as languages have evolved separately. For example, the Italian word “camera” means room, not the device you use to take photos. That would be “macchina fotografica.” Similarly, the word “fabbrica” in Italian means “factory” and not “fabric,” as you may have guessed.

| SP | PT | IT | FR | EN real meaning | EN cognate (false meaning) |

| actual | atual | attuale | actuel | current | actual |

| recordar | recordar | ricordare | rappeler | to remind | to record |

| enviar | enviar | inviare | envoyer | to send | to envy |

| librería | livraria | libreria | librairie | bookstore | library |

It can be useful to be familiar with these false friends to avoid some embarrassing errors. Here are some examples where the English cognate can give a false indication of the real meaning:

Negation

In general, forming the negation in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French is a simple procedure, without many exceptions:

- To form the negation in Spanish, we add “no” in front of the verb (and before any object pronoun before the verb).

- To form the negation in Portuguese, we add “não” /nãw/ in front of the verb (and before any object pronoun before the verb).

- To form the negation in Italian, we add “non” in front of the verb (and before any object pronoun before the verb).

- To form the negation in French, we add “ne” in front of the verb (and before any object pronoun before the verb) and “pas” after the verb.

Here are some examples:

| SP | No juego al fútbol. | I don’t play soccer. |

| PT | Não jogo futebol. | |

| IT | Non gioco a calcio. | |

| FR | Je ne joue pas au football. | |

| SP | No lo quiero. | I don’t want it. |

| PT | Não o quero. | |

| IT | Non lo voglio. | |

| FR | Je ne le veux pas. |

Double Negative in Romance Languages

In many cases, we can have a double negative in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French, without changing the meaning to affirmative. For example:

| SP | No quiero nada. | I don’t want anything. |

| PT | Não quero nada. | |

| IT | Non voglio niente. | |

| FR | Je ne veux rien. |

Notice that when another negation word is used in French, e.g., “jamais” (never), “rien” (nothing/anything), “personne” (nobody/anybody), “plus” (anymore), etc., it often replaces “pas” following the verb to form the negative. Here are some examples:

| Je n’ai rien fait de mal. | I didn’t do anything wrong. |

| Je ne vois personne ici. | I don’t see anybody here. |

| Il ne répond plus. | He doesn’t respond anymore. |

Notice that “ne” is contracted to “n’” before a vowel or a mute “h.” If a compound tense (a tense that uses an auxiliary verb) is used in French, the “ne … pas,” or a similar negative construction like the aforementioned examples, is placed around the first verb, that is, the auxiliary verb, e.g., “Je n’ai pas mangé” (I have not eaten).

Uses of the Written Accents in Romance Languages

Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French use written accents.

Written Accents in Spanish

The most important written accent in the Spanish language is the acute accent ( ´ ). In addition to marking the exceptions to the syllable stress rules, the acute accent has the following two uses:

- To distinguish between the meaning of words that would otherwise be written in the same manner. For example, “el” is the masculine definite article “the,” whereas “él” is the personal pronoun “he,” “mas” (formal use only) is a conjunction meaning “but,” whereas “más” means “more.”

- To distinguish between interrogative and relative pronouns, e.g., “¿Dónde vives?” (Where do you live?) vs. “No hay transporte donde vivo” (There is no transportation where I live). Notice that the interrogative pronoun “dónde” (where) has an accent on the vowel of the first syllable in the first example. The same concept applies to some other interrogative pronouns, such as “¿Quién?” (who?), “¿Qué?” (what?), “¿Cuál?” (which?), “¿Dónde?” (where?).

Written Accents in Portuguese

In Portuguese, there are five written accents: acute ( ´ ), grave ( ` ), circumflex ( ˆ ), tilde ( ͂ ), and cedilla ( ¸ ). Let us discuss each in more detail:

- Acute ( ´ ): This written accent can be found on any of the five vowels: “a,” “u,” “i,” “o,” or “e.” It indicates that the syllable should be stressed, and when used with “a,” “e,” or “o,” it also indicates an open sound.

- Circumflex ( ˆ ): The pointy hat-like accent can be used with any of the three vowels: “a,” “e,” or “o.” The circumflex indicates a closed sound and that the syllable should be stressed.

- Tilde ( ͂ ): The tilde can only appear on the letter “a” or “o” to denote nasal pronunciation. e.g., “nação” /na-sãw/ (nation), “põe” /põy / (he/she puts), etc.

- Grave ( ` ): The grave accent is often used to mark the contraction of two consecutive vowels, with the first vowel often being a preposition, e.g., “a” + “as” = “às” (at the). More details on this in Lesson 7 of this level.

- Cedilla ( ¸ ): This accent is used uniquely with the letter “c” to denote a soft “s” sound even though the letter is followed by “a,” “o,” or “u,” e.g., “maçã” (apple), “ação” (action), etc.

Written Accents in Italian

In Italian, there are two written accents: acute ( ´ ) and grave ( ` ). The only letters that can be accented in Italian are: “a,” “i,” “o,” “u,” and “e.” The letter “e” can take an acute “é” or grave “è” accent to indicate a closed or open vowel sound, respectively. The other four letters can only take a grave accent, i.e., “à,” “ì,” “ò,” and “ù.”

We have encountered one common use of the written accent in Italian, that is, to indicate stress on the last syllable of a word, e.g., “città” (city), “caffè” (coffee), “perché” (why), “ventitré” (twenty-three), etc. In general, the acute accent is used with causal conjunctions ending in “-ché,” e.g., “perché” (why) or compound words ending in “-tré,” e.g., “ventitré” (twenty-three), whereas in most other cases, the grave accent is used.

Another important use of written accents in Italian is to distinguish between the meaning of monosyllabic words that would otherwise be written in the same manner. For example, “e” is used as a conjunction meaning “and,” whereas “è” is the verb “to be” in the second-person singular form of the present tense, meaning “is.” Below are more examples:

| Word without accent | Meaning in English | Word without accent | Meaning in English |

| da | from | dà | gives |

| ne | of it | nè | neither |

| si | oneself | sì | yes |

| se | if | sè | himself/herself |

| la | the | là | there |

Another optional use of the written accent, that is optional, is to distinguish between different meanings of the same word depending on the syllable the stress falls on. For example, “principi” means “princes,” whereas “princìpi” means “principles.” Similarly, “ancora” is an adverb meaning “still,” whereas “àncora” means “anchor.” Remember that the use of the accent in these examples is optional, and the context can often determine the meaning without the need for an accent.

Written Accents in French

In French, there are five written accents: acute ( ´ ), grave ( ` ), circumflex ( ˆ ), dieresis ( ¨ ), and cedilla ( ¸ ). Let us discuss each in more detail:

- Acute ( ´ ): This can be found only on the letter “e.” It indicates a closed “e” sound. In some cases, especially at the beginning of some words, it may indicate that the word starts with “s” in the original Latin spelling. For example, “école” (school), “état” (state), “étudier” (to study), etc.

- Grave ( ` ): The grave accent is often found on the letters “a” and “e,” and in only one case on the letter “u,” that is “où” (where). If it appears on the letter “e,” it indicates an open “e” sound. Another use of the grave accent in French is to distinguish between the meaning of monosyllabic words that would otherwise be written in the same manner. For example, “a” is used as a third-person singular form of the verb “to have,” whereas “à” is a preposition that often means “at” or “in.” Similarly, “la” is used as a feminine singular definite article meaning “the,” whereas “là” means “there.”

- Circumflex ( ˆ ): The pointy hat-like accent can be used with any of the five vowels: “a,” “e,” “i,” “o,” or “u.” When used with “o,” it denotes closed “o” sound, whereas it denotes an open sound when used with “a” or “e.” In many cases, the circumflex can point to an “s” that was dropped after the circumflex letter from the original source language. For example, “forêt” (forest), “hôpital” (hospital), “côte” (coast), “pâté” (paste), “rôtir” (to roast), etc. Similar to the grave accent, the circumflex is sometimes used to distinguish between the meaning of monosyllabic words that would otherwise be written in the same manner. For example, “sur” is a preposition meaning “above,” whereas “sûr” is an adjective meaning “sure” or “certain.” Similarly, “mur” means “wall,” whereas “mûr” means “ripe” or “mature.”

- Dieresis ( ¨ ): The dieresis is a special accent that is often used on the second vowel of a two-vowel combination to denote that the two vowels must be pronounced separately. The dieresis is often found on the letter “e” or “i,” and in rare cases on the letter “u.” For example, “naïve” (naïve) is pronounced /na-eev/, not /nev/, despite the “ai” combination. Similarly, “Noël” (Christmas) is pronounced /no-el/, not /neul/, despite the “oe” combination.

- Cedilla ( ¸ ): This accent is used uniquely with the letter “c” to denote a soft “s” sound even though the letter is followed by “a,” “o,” or “u,” e.g., “français” (French), “garçon” (boy), “ça” (this), “leçon” (lesson), “reçu” (receipt), “façon” (way or method), and “façade” (façade).

Punctuation

In general, punctuation marks in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French are used the same way as in English. One notable exception is the following:

- Interrogation and exclamation marks are used in Spanish both at the beginning and at the end of the question or exclamation with the inverted sign at the beginning, such as “¿Cómo estás?” (How are you?) and “¡Qué lástima!” (What a pity!).

Notice that this rule is not always enforced in many countries except in formal and legal documents.

Statements vs “Yes/No” Questions

Punctuation is also important to distinguish a question from a statement in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French. For instance, the following sentence is a statement:

| SP | Tú hablas inglés. | You speak English. |

| PT | Você fala inglés. | |

| IT | Tu parli inglese. | |

| FR | Tu parles anglais. |

Adding a question mark to the end of the sentence (and adding an inverted question mark to its beginning in Spanish only) makes it a question:

| SP | ¿Tú hablas inglés? | Do you speak English? |

| PT | Você fala inglês? | |

| IT | Tu parli inglese? | |

| FR | Tu parles anglais? |

This is one way to form a “yes” or “no” question in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French. Obviously, the intonation needs to change in the spoken language.

Another way to form a “sì” (yes) or “no” (no) question from a statement in Italian is to place the subject to the end. For example, “È caldo il caffè?” (Is the coffee hot?).

Another more formal way to form a “oui” (yes) or “non” (no) question from a statement in French is to place the phrase “Est-ce que” before the statement. For example, “Est-ce que tu parles français?” (Do you speak French?). The introductory phrase “Est-ce que…” translates literally as “Is it that …”

Another way to form a “oui” (yes) or “non” (no) question from a statement in French is called inversion. The subject pronoun and the verb are inverted and a hyphen is placed in between. For example, “Parles-tu français?” (Do you speak French?). This method is more common in written language. Notice that inversion requires a subject pronoun such as “je” (I), “tu” (you), or “il/elle” (he/she/it). If the subject is a noun instead of a subject pronoun, the subject is maintained and repeated using the proper subject pronoun, e.g., “Le café, est-il chaud” (Is the coffee hot?). If a verb that ends in a vowel precedes “il/elle” (he/she/it) or “on” (we/one), the letter “t” must be added before the subject pronoun that begins with a vowel, e.g., “Parle-t-il français?” (Does he speak French?).

We do not use any auxiliary to reorder the sentence using the English approach to form a question.

Contractions

There are only two contractions in Spanish that involve the singular masculine definite article “el,” and, unlike in English, these contractions are not optional:

| a + el = al | e.g., “Yo voy al restaurante” (I go to the restaurant). |

| de + el = del | e.g., “Yo vengo del café” (I come from the café). |

In Portuguese and French, all contractions are also mandatory.

In Italian, some contractions are mandatory, such as “l’acqua” (the water), while others are optional. For example, “dove è” (where is) is optionally contracted as “dov’è.” Unfortunately, there is no universal rule. You will know which contractions are optional as you practice and go through the lessons.

Abbreviations

The concepts behind the formation of acronyms and abbreviations in Romance languages are very similar to those in English. One notable exception is the doubling of the letters in the abbreviation of some plural nouns in Spanish and Italian. For example, in Spanish, “Estados Unidos” (United States) is abbreviated as “EE. UU.” Similarly, in Italian “Poste e Telegrafi” (Posts and Telegraphs) is abbreviated as “PP. TT.”

Capitalization

The words are capitalized in cases almost identical to those in English, with a few notable exceptions that are not capitalized in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French, mainly:

- Adjectives of nationalities and languages, for example:

| SP | italiano | Italian |

| PT | italiano | |

| IT | italiano | |

| FR | italien | |

| SP | canadiense | Canadian |

| PT | canadense | |

| IT | canadese | |

| FR | canadien | |

| SP | español | Spanish |

| PT | espanhol | |

| IT | spagnolo | |

| FR | espagnol |

- Days and months, for example:

| SP | martes | Tuesday |

| PT | terça-feira | |

| IT | martedì | |

| FR | mardi | |

| SP | enero | January |

| PT | janeiro | |

| IT | gennaio | |

| FR | janvier | |

| SP | julio | July |

| PT | julho | |

| IT | luglio | |

| FR | juillet |

Back to: Comparative Grammar Lessons

Other lessons in Level I: