Luckily, Portuguese uses the Latin letters used in English with only a few differences in pronunciation. Portuguese, unlike English, is a phonetic language, meaning that you should be able to pronounce any written word without the need for a dictionary.

Table of Contents

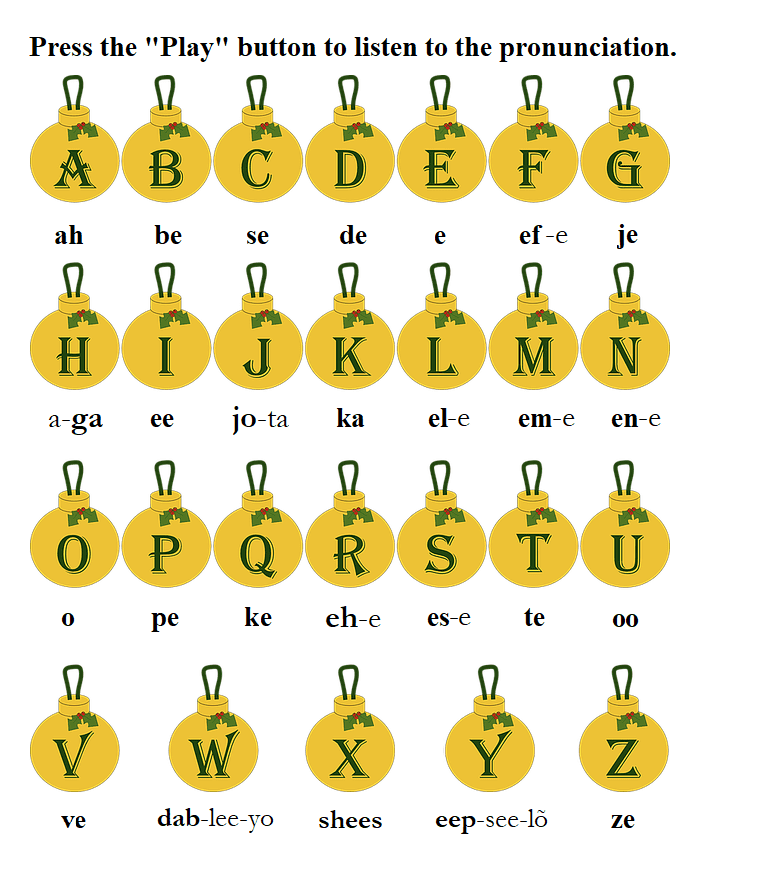

Alphabet

Start with the Portuguese alphabet in the table below and use your Anki cards to anchor what you have learned via spaced-repetition exercises.

| Portuguese Letter | Pronunciation(1) | Notes | |

| A | a | ah | like “a” in “father” |

| B | b | be | equivalent to English “b” |

| C | c | se | sounds like English “k,” except: 1. before “e,” “i,” or “y,” it sounds like “s” 2. if written with a cedilla “ç,” it sounds like “s” 3. before “h,” “ch” sounds like “sh” in “sheep” |

| D | d | de | equivalent to English “d,” except before “i” or unstressed “e,” where it sounds like “j” in “joy” |

| E | e | e | can be an open sound like “e” in “bet” or closed sound like “a” in “say” (without the final “y”) |

| F | f | ef-e | equivalent to English “f” |

| G | g | je | sounds like “g” in “get,” or like the sound of “s” in “measure” or “conversions” |

| H | h | a-ga | silent letter like “h” in “hour,” except when preceded by “l” to form “lh,” where it sounds like “lli” in “million,” or by “n” to form “nh,” where it sounds like “ny” in “canyon” |

| I | i | ee | like “ee” in “see” or “i” in “marine” |

| J | j | jo-ta | like the sound of “s” in “measure” |

| K | k | ka | equivalent to English “k” (only in loan words) |

| L | l | el-e | equivalent to English “l,” except before a consonant or at the end of a word, where it sounds like “w” in “row” |

| M | m | em-e | equivalent to English “m,” except when nasal |

| N | n | en-e | equivalent to English “n,” except when nasal |

| O | o | o | equivalent to English “o,” and can have an open or closed sound |

| P | p | pe | equivalent to English “p” |

| Q | q | ke | always followed by “u” to form “qu” which sounds like “kw” except before “e” or “i,” where “qu” often sounds like “k” |

| R | r | eh-e | like English “r” but rolled with a single flap against the upper palate, except: 1. at the beginning of a word, after “l” or a nasal sound, or when doubled “rr,” it sounds like “h” 2. at the end of word, it is often not pronounced |

| S | s | es-e | pronounced like “z” in “zoo” if the “s” is placed between two vowels or before a voiced consonant (b, d, g, l, m, n, r, v); otherwise, it is pronounced like “s” in “sea” |

| T | t | te | like “t” in “tale,” except before “i” or unstressed final “e,” where it sounds like “ch” in “cheese” |

| U | u | oo | like “oo” in “food” |

| V | v | ve | equivalent to English “v” |

| W | w | dab-lee-yo | equivalent to English “w” (only in loan-words) |

| X | x | shees | 1. like “sh” in “shop” at the beginning of a word or between vowels in most cases 2. like “s” in “sea” before “c,” “f,” “p,” “t,” or “qu,” in addition to few other words 3. like “z” in words beginning with “ex” 4. like “ks” in some words |

| Y | y | eep-see-lõ | equivalent to English “y” (only in loan-words) |

| Z | z | ze | equivalent to English “z,” except at the end of a word, where it can sound like “z” or “s” |

Throughout the lessons we will use slash marks “/” to mark the pronunciation of some words, and we will highlight the stressed syllable in bold. This is in case of multi-syllable words, such as, “falar” /fa-la/ (to speak).

Consonants

- The letters “k,” “w,” and “y” are only found in foreign words used in Portuguese.

- The letter “c” in Portuguese is used to form the equivalents of the sounds “k,” “s,” and “sh” in English. The way this is achieved is as follows:

- If the letter “c” is followed by “e” or “i,” it is considered a soft “c” and is pronounced like “s” in “sea,”e.g., “cinema” /see-ne-ma/ (cinema).

- If the letter “c” is written with a cedilla, i.e., “ç,” it is considered a soft “c” and is pronounced like “s” in “sea,”e.g., “caça” /ka-sa/ (hunting). The cedilla is always followed by a vowel other than “e” or “i.”

- The “ch” combination in Portuguese is pronounced like “sh” in “sheep,”e.g., “chamar” /sha-ma/ (to call).

- Otherwise, the letter “c” is considered a hard “c” and is pronounced like “k” in “kit,”e.g., “café” /ka-fe/ (coffee).

Notice that “ch” combination in Portuguese is pronounced like “sh” in “sheep.” To summarize:

| c | + | “e” or “i” | soft “c” | “cinema” /see-ne-ma/ (cinema) |

| ç | + | “a,” “o,” or “u” | soft “c” | “maça”/ma-sa/ (apple) |

| c | + | “h” | “sh” sound | “chamar” /sha-ma/ (to call) |

| c | + | any letter other than “e,” “i,” or “h” | hard “c” | “café” /ka-fe/ (coffee) |

- The letter “d” is pronounced like an English “d,” except before “i” or an unstressed final “e,” where it sounds like “j” in “joy,” e.g., “dia” /jee-ya/ (day), “sede” /se-ji/ (thirst), etc.

- The letter “g” can also have a hard sound like “g” in “gab” or a soft sound like “s” in “measure.” The basic rules are:

- If the letter “g” is followed by “e” or “i,” it is considered a soft “g” and is pronounced like “s” in “measure,” e.g., “geral” /je-raw/ (general).

- If the letter “g” is not followed by “e” or “i,” it is considered a hard “g” and is pronounced like “g” in “gab,” e.g., “gás” /gas/ (gas).

Notice that the letter “u” is mute when it falls between the letter “g” and “e” or “i” to maintain the hard “g” pronunciation, e.g., “guerra” /ge-ha/ (war), “guitarra” /gee-ta-ha/ (guitar), etc.

There are a few words in which “gu” is pronounced like the English “gw” sound before “e” or “i,” e.g., “aguentar” /ag-wẽ-ta/ (to withstand or put up with).

To summarize:

| g | + | “e” or “i” | soft “g” | “gelo” /je-lo/ (ice) “geral” /je-raw/ (general) |

| g | + | any letter other than “e” or “i” | hard “g” | “gás” /gas/(gas) “guia” /gee-ya/(guide) |

- The letter “h” is generally not pronounced in Portuguese, e.g., “hoje” /o-je/ (today), except in the following cases:

- When “h” is preceded by “c” to form the combination “ch,” which forms the equivalent English sounds “sh,” e.g., “chegar” /she-ga/ (to arrive).

- When “h” is preceded by “n” to form the combination “nh,” which is pronounced like “ny” in “canyon,” e.g., “lenho” /le-nyo/ (wood).

- When “h” is preceded by “l” to form the combination “lh,” which is pronounced like “lli” in “million,” e.g., “olho” /o-lyo/ (eye).

- The letter “l” is equivalent to the English “l,” except at the end of a word where it sounds like “w” in “week,” e.g., “sal” /saw/ (salt), “Brasil” /bra-zeew/ (Brazil), etc.

- The letter “q” is always followed by the letter “u” and sounds like “kw” before “a” and “o,” and like “k” before “e” and “i,” e.g., “quatro”/kwa-tro/(four), “quilo”/kee-lo/(kilo). In only a few words, the “qu” is pronounced like the English “kw” sound before “e” or “i,” e.g., “equestre” /ek-we-stre/ (equestrian).

- The letter “r” is equivalent to the English “r” but rolled with a single flap against the upper palate, “caro” /ka-ro/ (expensive), except in the following two cases:

- At the beginning of a word, after a nasal sound or “l,” or when doubled “rr,” the “r” sounds like “h,” e.g., “carro” /ka-ho/ (car), “rato” /ha-to/ (mouse), “genro” /jẽ-ho/ (son-in-law), etc.

- At the end of a word, the “r” is sometimes not pronounced, e.g., “comer” /ko-me(r)/ (to eat), depending on the regional variant of Brazilian Portuguese.

- The letter “s” can sound like English “s” or “z.” If the “s” falls between two vowels or before a voiced consonant (b, d, g, l, m, n, r, v), it is pronounced like “z” in “zoo.” Otherwise, it is pronounced like “s” in “sea.” In some parts of Brazil, the final “s” is pronounced like “sh” in “sheep,” e.g., “anos” /a-nosh/ (years).

- The letter “t” is pronounced like an English “t” in “top,” except before “i” or an unstressed final “e,” where it sounds like “ch” in “chip,” e.g., “tia” /chee-ya/ (aunt), “brilhante” /bree-lyã-chi/ (brilliant), etc.

- The letter “x” has four possible pronunciations in Portuguese:

- Like “sh” in “shop” at the beginning of a word or between vowels in most cases. This is the most common possible pronunciation. Examples include: “xale” /sha-li/ (shawl), “xerife” /she-ree-fi/ (sherriff), “peixe” /pey-shi/ (fish), “baixo” /bay-sho/ (low), etc.

- Like “s” in “sea” before “c,” “f,” “p,” “t,” or “qu,” e.g., “extra” /es-tra/ (extra), in addition to few other words, such as: “próximo” /pro-see-mo/ (next), “máximo” /ma-see-mo/ (maximum), “auxílio” /aw-see-lyo/ (aid), “sintaxe” /sĩ-ta-si/ (syntax), and “trouxe” /troo-si/ (he brought).

- Like “z” in many words beginning with “ex” followed by a consonant or a voiced consonant (b, d, g, l, m, n, r, v), e.g., “exame” /e-za-mi/ (exam), “ex–marido” /ez ma-ree-do/ (ex-husband), etc.

- Like “ks” in some words, e.g., “taxi” /ta-ksee/ (taxi), “axila” /a-ksee-la/ (armpit), “complexo” /kõ-ple-kso/ (complex), “fixo” /fee-kso/ (fixed), “ortodoxo” /or-to-do-kso/ (orthodox), “óxido” /o-ksee-do/ (oxide), “reflexo” /ref-le-kso/ (reflex), “sexo” /se-kso/ (sex), “tóxico” /to-ksee-ko/ (toxic), etc.

- The letter “z” is pronounced like an English “z,” except at the end of a word, where it can sound like “z” or “s” depending on the regional dialect, e.g., “luz” /looz/ or /loos/ (light).

- The only double consonants that occur in Portuguese are “rr” and “ss,”, which are pronounced like “h” in “hot” and “s” in “set,” respectively.

Syllable Stress in Portuguese

As mentioned earlier, Portuguese is a phonetic language. If you practice enough, you should eventually be able to pronounce any Portuguese word without listening to an audio transcription or referring to a dictionary. At the start, some beginner Portuguese learners complain that most Portuguese learning books do not have a phonetic transcription. Hopefully they come to realize that once you learn some basic rules, combined with sufficient practice, it will become easier.

Knowing which syllable to stress in Portuguese is critical to speaking comprehensibly and achieving fluency. The good news is that, unlike in English, where syllable stress seems more arbitrary, there are well-established rules in Portuguese which eliminate the need for guessing. It is important to ensure that you master these rules early on as you build your vocabulary. The three main rules are:

- If the last letter is “a,” “o,” or “e” (after removing any final“s,” “ns,” or “m”), the stress falls on the second-to-last syllable, also called the penultimate syllable. For example, “fatura” (invoice) /fa-too-ra/, “bracelete” (bracelet) /bra-se-le-chi/, “falam” (they speak) /fa-lã /, etc. The stressed syllable in the pronunciation script is in bold.

- If the last letter is not “a,” “o,” or “e” (after removing any final“s,” “ns,” or “m”), the stress falls on the last syllable. For example, “azul” (blue) /a-zoow/, “abril” (April) /ab-reew/, “falar” (to speak) /fa-lar/.

- If the word has an acute accent ( ´ ), a circumflex ( ^ ), or a tilde ( ~ ), this overrides the two previous rules, and we simply stress the syllable that contains the accent or the tilde. For example, the word “inglês” (English), if not marked by an accent, following the first rule, would be pronounced as “ĩ-gles.” However, the accent on the second syllable overrides that rule and necessitates that we pronounce it correctly as “ĩ-gles.” Other examples include “útil”(useful) /oo-cheew/, “fácil”(easy) /fa-seew/, and “médico” (doctor) /me-dee-ko/.

There are two exceptions to the last rule:

- If a word has both a tilde and an acute or circumflex accent, the stress falls on the syllable with the acute or circumflex accent, e.g., “bênção” /bẽ-sãw/ (blessing), “órgão” /or-gãw/ (organ), etc.

- In words that have suffixes, e.g., “-mente,” “-zinho,” etc., the tilde does not indicate stress when it falls before the second-to-last syllable, e.g., “irmãmente” /eer-mã-mẽ-chi/ (sisterly), “Joãozinho” /jwãw-zĩ-nyo/ (diminutive of “João”), etc.

Other Lessons in Level I: